The Art Problem:

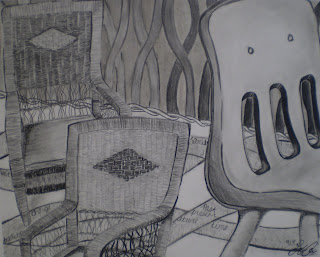

The Art Problem:This Creative Challenge invites students to express something about their personal "emotional baggage" in a poetic and somewhat ambiguous way using drawings of common objects on top of prepared grounds. Photocopies of luggage drawings (whole pieces and details) are submerged in grounds prepared with newsprint and ink washes. On top, students draw and paint objects that, in themselves and through their relationships with each other, symbolize what lies at the crux of each student's "emotional baggage."

Materials:

A variety of suitcases (I borrowed them from our choral director's props storage)Sketchbook or sketch paperPencilEraserPaper (we used a tall vertical—or horizontal—stony medium gray paper)

Tape (to tape margins of paper)

Newsprint

Matte medium or ever-so-slightly watered down glue

Black India ink (diluted)

Symbolic objects (brought from home or pilfered from still-life storeage)

White acrylic paint

Brushes, water, containers

Ebony pencils

After first day of Challenge, you will need photocopies of students’ drawings of suitcases (whole pieces and details; I asked them to choose their best two and I made small, medium and large copies of each). Note: If you prefer to save time and paper, students can use their actual drawings, but copies in different sizes are nice for unity.

Embroidery floss in a variety of colors (I bought a couple of inexpensive variety packs)Embroidery Needles

Prerequisites: An understanding of and sketchbook practice with modeling techniques (hatching, cross-hatching, stippling, cross-contour marks, etc.)

Familiarity with "weighted line" (widened and tapered line) and varied line quality

Knowledge of a value scale

Basic understanding of composition and Elements and Principles of Design

Individual Student Procedures:

Class 1

1. Discuss definition of "emotional baggage"— ideas, beliefs, or practices retained from one’s

previous life experiences, especially insofar as they affect a new situation in which they may be no longer relevant or appropriate.

2. Students to write an entry in their sketchbooks about their personal emotional baggage. (If you want to give them the option of keeping it private, have them tape a "cover sheet" over it.) 3. Students make a series of approximately six 5-minute gesture drawings of whole suitcases or details, aka "the baggage," at a series of drawing stations—suitcases set on tables with a few chairs gathered around. (We used white drawing paper and thick graphite sticks, but you could use whatever you prefer.)

4. Students choose their favorite two drawings for teacher to photocopy, if using photocopies.

5. Homework: students bring objects from home to symbolize their emotional baggage (or they can scavenge them from still-life storage).

Class 2: Prepared Grounds

1. Students tape edges of their paper (they should stick masking tape on their clothes to remove a little of the adhesive and then lay along edges of paper).

2. Using matte medium or glue with a drop or two of water, students adhere 3 pieces of newsprint to their paper support, by brushing under and on top of newsprint. Small sponge brushes work well.

3. Next, students wash over their ground with a medium ink wash.

4. Then, students cut out their suitcase drawings and, using matte medium or very slightly diluted glue, adhere them in an interesting way to their support to create movement, repetition, unity and variety.

5. While grounds are drying, students should being work on their thumbnail sketches. The tricky part is helping students draw a thumbnail in which they indicated the lines and shapes established in their prepared grounds.

6. If desired, students can practice modeling the objects they have chosen.

Class 3 and 4 (maybe more): Developing Compositions

1. To begin building up drawings on their grounds, students may block out areas with black ink to create separation between object and ground and, once dry, work on top. Or, they may work directly on the ground and add later add a black ink halo for separation.

2. In either case, to create objects, students lightly sketch the contours first in whatever media will show up and then paint the silhouettes solid white. Once dry, students use Ebony pencil to model the form of the objects, striving for drama through a wide range of values.

Class 5 and 6 (maybe more): Color 1. Students choose complementary colors of acrylic and dry brush them on to create additional layers of movement, unity, variety and emphasis.

2. As a finishing touch, students use embroidery thread in one or both colors—or even twist them together—and stitch into their pieces using restraint to develop the movement, unity, variety and emphasis even further. (They can use any type of stitching they choose, though mimicking that of the luggage can be effective and is, in fact, what inspired the use of thread.)

3. Finally, students may work back into compositions, if desired, to make any adjustments using any of the materials used so far plus, e.g. white and colored pencils.

Student Extension—Group Critique:

Prior to the critique, students put their names in a box and then draw a name other than their own. Then they fill out a

Critique Form based on the work created by the student whose name they drew. They will refer to this form during the Critique. (This ensures that the critique moves along with no one grasping for something to say.) Next, students and teacher sit in a circle for the Critique during which each student, in turn, addresses at least 3 aspects of the work s/he critiqued, preferably a balance between "glows" (strengths) and "grows" (areas of improvement). After each student presents, the student whose work was critiqued is given an opportunity to address aspects of his or her work. Similarly, other students may comment.

Assessment:Score and comment on pieces according to the

"Sailing the 7 Cs" visual arts rubric

IB-MYP Area of Interaction: Health and Social

Image Credits (top to bottom): Stephanie B., Paula L., Grace M., Maggie Q., Annaelle S., Kendria T., and Teacher Sample, Betsy DiJulio, NBC Art Teacher, Princess Anne High School, Virginia Beach, VA.

Just before the Thanksgiving Holiday, I used these images of "Freedom from Want" by Norman Rockwell as prompts for an art criticism mini-lesson. I simply projected them, provided the following information for note-taking and asked students to work individually or in small groups to answer two questions before we discussed them as a class. I found it to be a simple, quick and effective art criticism "hook," and hope you do too.

Just before the Thanksgiving Holiday, I used these images of "Freedom from Want" by Norman Rockwell as prompts for an art criticism mini-lesson. I simply projected them, provided the following information for note-taking and asked students to work individually or in small groups to answer two questions before we discussed them as a class. I found it to be a simple, quick and effective art criticism "hook," and hope you do too.